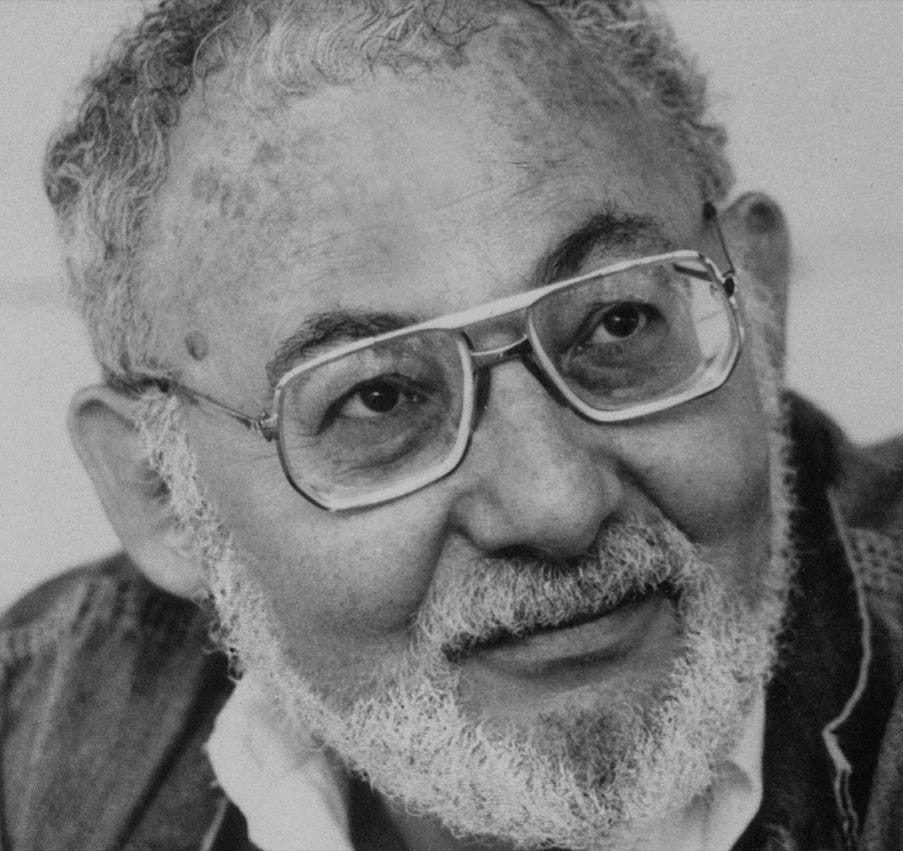

If you're not a deep-in-the-weeds lit’ry type, or if you're a kid, you might not have heard his name. Elkin’s first novel was published when, speaking of kids, I was nine years old. He was one of my idols, starting in my teen years and still today.

How to describe Elkin’s prose? Gimlet-eyed, often comic, reliably baroque, wonderfully overwrought. He appreciated wisecracks. The prolific Elkin’s work has stood up to history as well as, say, that of William Gass, his professor colleague in the English department at Washington University in St. Louis.

That morning in 1991, his wife Joan showed me into the house. I found Stanley at the kitchen table in his wheelchair, finishing up a bowl of cereal. We said hellos. Joan brought him half a grapefruit, which he lifted to his face and chomped into violently.

At first I thought the scene was (a) erotic, the way he cupped the fruit in both hands, and the slurping, the juice dripping to his elbows and (b) maybe contrived for the purpose of shocking me. I'd heard stories about Elkin’s trickster side.

Joan stood by, in the ready posture of a person who has taken care of a chronically ill spouse for a long time. Multiple sclerosis.

At last Joan helped him towel off and he sat back, arms crossed. “Go ahead, ask your questions,” he said. And for the next 10 or 15 minutes I did. He gave yes-no answers, or a terse fragment. He took a thumbnail to something stuck between his teeth. “These questions are so old,” he sighed. At one point he fixated on my watch and asked where I got it.

Toward the end, Elkin said wearily, “I wish you would just leave.” So I tucked away my notepad and did. Before slinking away, I told him that i hoped he felt better soon. A lot of people want more stories from Stanley Elkin. “There won’t be many more,” he said. “Because I’m going to die!”

Joan, embarrassed, showed me to the door.

I had no way of predicting how people would behave or how I would behave in response, or what kind of steam we would make together before flying apart.

Today, I feel the same.

At the office, our photographer told me that when he visited Elkin to get images for the newspaper piece, the author was still railing about me – “your reporter and his sycophantic bullshit.” Harumph! The photographer, who hated me, passed this along with obvious glee.

I told Cliff, my editor, that there would be no Elkin article.

About two weeks later, I was paged on the PA system. “Stanley Elkin on line two.” Oh no, I thought, Is he not done with me?

Elkin’s voice was level, friendly. “My wife informed me that I was immensely rude to you during your visit,” he said. “I was wondering if you had anything further I might help with.”

Was this … damage control? He, or his wife, or publisher, may have fretted about what I would write about our disastrous meeting, an unflattering profile just as his latest novel, The MacGuffin (which would become a finalist for the National Book Award), arrived in stores. True, our little alternative weekly couldn’t have done much damage – but every sale counted, even in those days.

For about half an hour, we conducted an impromptu back-and-forth. I tried the same, so old questions as before, which this time gained complete responses, eloquent and wry. I asked Elkin if he had an idea for his next novel. He said yes, and the title was Van Gogh’s Room at Arles. I asked what it was about. His tone went lower. “I don't know,” he said. “All I have is the title.” The last thing he said to me was, “See you in the funny papers.”

There would be an Elkin article after all.

Penciling through it, Cliff asked, “Do you want to leave in the grapefruit scene?”

Yes, I said. Immediately.

“I thought so,” Cliff sighed the way I’d heard Elkin sigh at my questions, so old.

Two years later, I was browsing the fiction aisle at Borders and saw the book, with Van Gogh’s painting of his room in the Yellow House in Arles that he rented with Gauguin.

Not until later did I get around to reading the 1994 edition of Best American Essays, where I found more by Elkin — a piece that had been published in Harper’s the year before, around the same time as Van Gogh’s Room at Arles (a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award). Called “Out of One’s Tree,” the essay had to do with the period in 1991 when he temporarily lost his mind. The period, that is, when I had dropped by to interview him.

At first, he hadn’t understood the medical cause, Elkin wrote. He’d been living a “by the numbers” existence necessary for his art. “How is it, then,” he wrote, “that in mid-April 1991 I forgot how to shower?”

He had accidentally overdosed on prednisone.

In Harper’s, Elkin laid out the whole story. “The only objective written report of my behavior that exists” from the blacked-out prednisone interval was my profile of him. In about the middle of the essay, he cited nine paragraphs of my Riverfront Times article. The grapefruit scene. He named the newspaper, but not me.

Right away I started ransacking my files for Elkin’s contact info. I would call him up. I would rib him for wrecking my one chance to get into Best American Essays. On his coattails. Wisecracks we would exchange! So far had we come from the funny-papers days. So old we had grown.

I found out that he was dead.

I love this piece. Not to give any sycophantic bullshit.

I have long carried around with me the worry that I killed Gene Roddenberry (creator of Star Trek), as I was the last to interview him for this biographical encyclopedia I was working for at the time. And then I did the same for Roald Dahl. It was all the luck of the draw. Like everything else in life, it’s not about me.